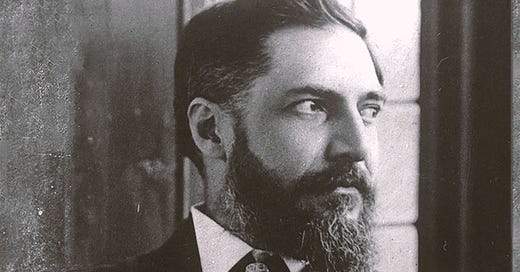

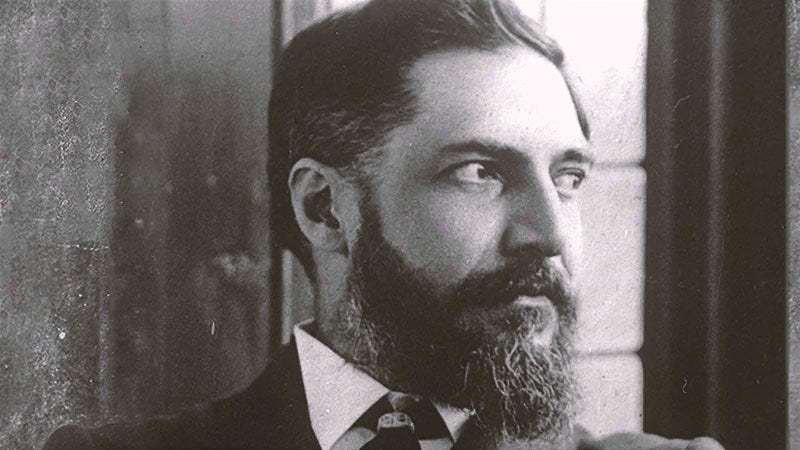

The Hawara archaeological site, home to the enigmatic Labyrinth of Egypt, has captivated explorers and scholars for centuries. Among the many expeditions that sought to unravel its mysteries, the work of Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie in the late 19th and early 20th centuries stands out as particularly groundbreaking. His meticulous excavations and innovative methodologies not only advanced the field of Egyptology but also provided critical insights into the Labyrinth, a structure described by ancient authors like Herodotus as one of the wonders of the ancient world.

Previous Expeditions: Setting the Stage for Petrie

Before Petrie's arrival, Hawara had already attracted the attention of several explorers and archaeologists, each contributing fragments of knowledge about the site:

Napoleon's Expedition (1799–1801): The French team documented the Hawara pyramid and the surrounding area, though they mistakenly identified some ruins as the Labyrinth. Their work, published in Description de l'Égypte, laid the groundwork for future studies but was limited by the technology and methodologies of the time.

Karl Richard Lepsius (1843): Leading a Prussian expedition, Lepsius conducted extensive excavations at Hawara, focusing on the cemetery and the area around the pyramid. He believed he had found parts of the Labyrinth, though later research revealed these to be Roman tombs. Despite this error, Lepsius's detailed records and maps provided valuable context for Petrie's later work.

Luigi Vassalli (1862): Vassalli searched for the pyramid's entrance and excavated parts of the necropolis, though his efforts yielded limited results. His work, however, highlighted the challenges of excavating Hawara, where layers of history were densely interwoven.

These early expeditions, while pioneering, were hampered by a lack of systematic methodology and the prevailing assumption that the Labyrinth had been completely destroyed. It was against this backdrop that Flinders Petrie arrived at Hawara in 1888, determined to apply his rigorous scientific approach to the site.

Petrie's Revolutionary Work at Hawara

Petrie's excavations at Hawara were transformative for several reasons:

Systematic Methodology: Petrie introduced systematic recording techniques, including precise measurements, detailed sketches, and careful stratigraphic analysis. This allowed him to distinguish between different layers of occupation and identify the remains of the Labyrinth beneath the rubble of later Roman settlements.

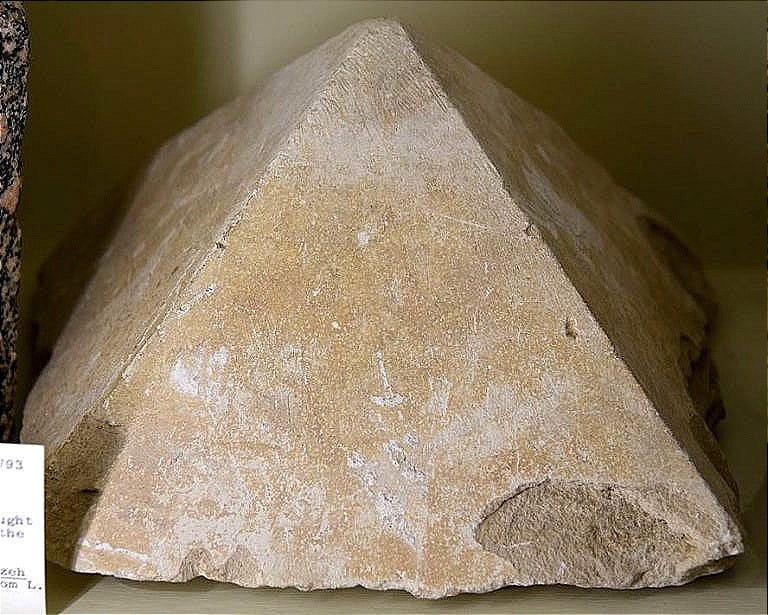

Identification of the Labyrinth's Foundation: Petrie discovered a vast artificial stone platform measuring approximately 304 meters by 244 meters, which he interpreted as the foundation of the Labyrinth. He argued that the structure itself had been dismantled in antiquity, its stones repurposed for other buildings. This theory, while contested, provided the first tangible evidence of the Labyrinth's existence and scale.

Discovery of the Fayum Portraits: While excavating the Roman-era cemeteries north of the pyramid, Petrie uncovered the now-famous Fayum mummy portraits. These lifelike paintings, dating to the Roman period, are among the earliest examples of portraiture in art history and offered a glimpse into the multicultural society of Graeco-Roman Egypt.

Challenging Prevailing Assumptions: Petrie's work debunked earlier claims, such as Lepsius's identification of Roman brick chambers as part of the Labyrinth. By demonstrating that these were later constructions built atop the Labyrinth's ruins, Petrie clarified the site's complex stratigraphy.

Reevaluating Petrie’s Conclusions on the Labyrinth’s Fate

Petrie’s work at Hawara fundamentally reshaped understanding of the Labyrinth’s physical remains. While his predecessors, like Lepsius, had misidentified Roman-era ruins as part of the Labyrinth, Petrie demonstrated that the true foundation of the ancient complex was a massive artificial stone platform measuring 304 meters by 244 meters—far larger than any known Egyptian temple. His meticulous documentation proved that the Labyrinth had once stood on this site, aligning with Herodotus’s descriptions of its grandeur.

However, Petrie concluded that the superstructure itself had been dismantled and repurposed as a quarry in later periods, leaving only the foundation and scattered stone fragments. This theory, while plausible, was based on surface-level evidence. Crucially, Petrie did not excavate beneath the platform, leaving open the possibility that the Labyrinth’s most legendary feature—its vast underground chambers, as described by classical authors—might still remain intact below.

Recent geophysical surveys, such as the 2008 Mataha Expedition, a cooperation by the NRIAG (Helwan) & the Ghent University, have detected grid-like subterranean structures beneath Petrie’s foundation, suggesting that the Labyrinth’s underground sections did persist, buried and untouched. This means Petrie was both right and incomplete: while the upper levels were indeed stripped away, the heart of the Labyrinth—the labyrinthine halls and chambers that awed ancient visitors—still lie hidden, awaiting excavation.

This underscores the urgency of revisiting Hawara with a new archaeological expedition, not only to preserve the Hawara Archaeological site, but to finally answer the question that eluded all historic explorers: How much of the colossal Labyrinth of Egypt still survives beneath the sands, and what ancient knowledge does it hold for humanity?

The Flinders Petrie Archives at University College London (UCL)

The extensive research materials from Sir William Matthew Flinders Petrie’s excavations at Hawara—including field notes, sketches, photographs, and artifact records—are preserved in the Petrie Museum of Egyptian and Sudanese Archaeology at University College London (UCL). This archive serves as an invaluable resource for scholars studying the Labyrinth of Egypt and the broader archaeological history of Hawara. UCL’s archives underscore the importance of preserving and re-examining historical fieldwork with new technologies. Scholars are encouraged to explore these resources to advance the study of Hawara’s Labyrinth—a task Petrie himself would have championed.

To access Petrie’s Hawara archives, visit the Petrie Museum UCL or explore their digital collections.

For those interested in learning more about the modern efforts to explore the Labyrinth, the findings of the Mataha Expedition are detailed in the following document: labyrinthofegypt_com__printversion.pdf > [https://drive.google.com/file/d/1YqntaYOhvSWA7fd3jFYToPqx34odntjB/view]