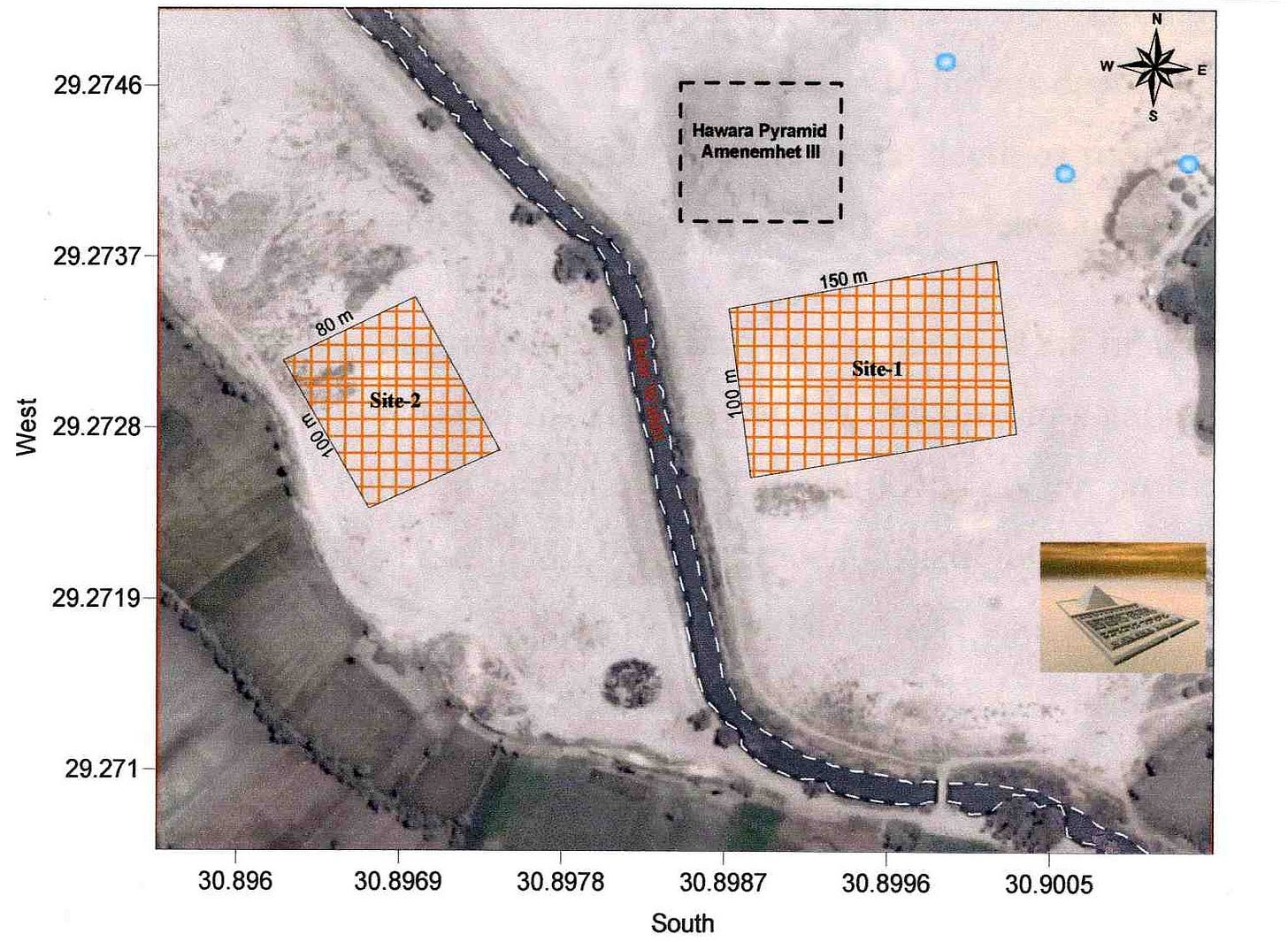

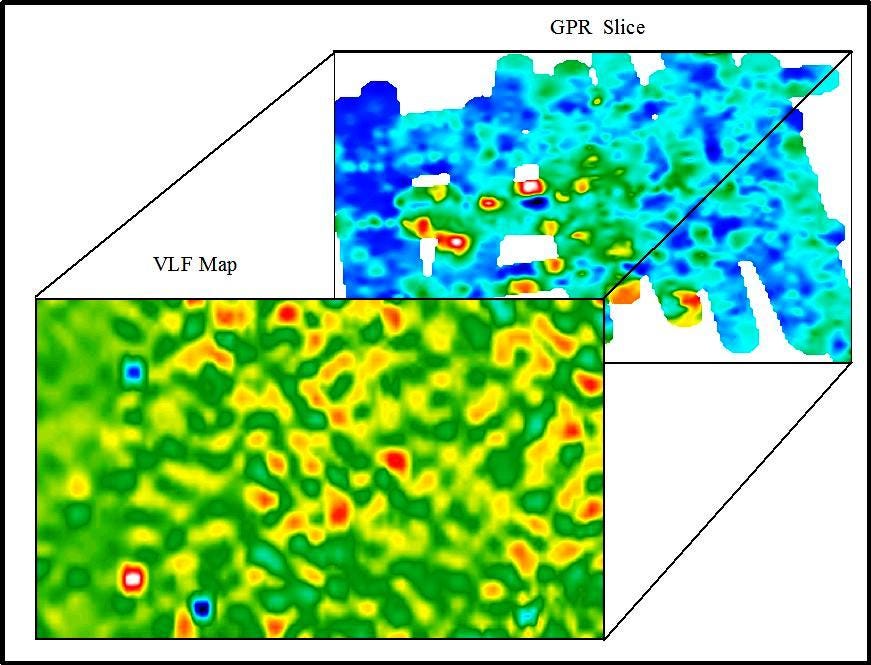

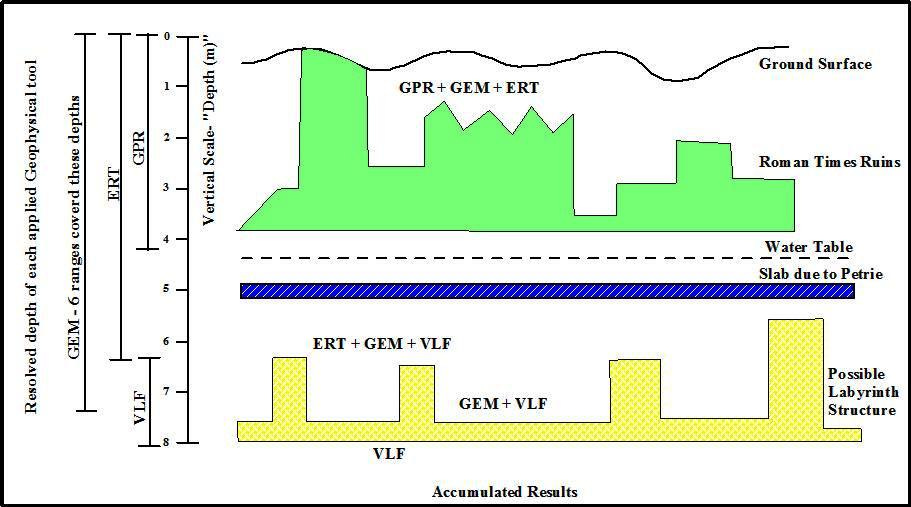

The Mataha-Expedition, conducted in 2008 at Hawara, Egypt, has unveiled a groundbreaking revelation about the legendary "Lost Labyrinth" of Egypt, challenging long-held assumptions from early explorers. Contrary to the belief that this colossal temple, celebrated by ancient authors such as Herodotus and Strabo as a vast stone library of the ancient world, was destroyed in antiquity—perhaps as a quarry in Ptolemaic times—the expedition's geophysical surveys demonstrate that significant human-made structures remain intact deep beneath the sands of Hawara. Utilizing advanced techniques like ground-penetrating radar (GPR), electrical resistivity tomography (ERT), and very low frequency (VLF) surveys, the team, a collaboration between the National Research Institute of Astronomy and Geophysics (NRIAG), Ghent University, and Louis De Cordier1, confirmed the presence of a massive grid of vertical walls, some several meters thick, forming nearly closed rooms at depths of 8 to 12 meters below the surface. These findings, spanning hectares south of the Hawara Pyramid of Amenemhet III, align with historical descriptions of the Labyrinth as an architectural marvel surpassing even the pyramids, with its endless stone walls potentially preserving the knowledge of ancient Egypt.

This discovery is not only one of the most thrilling archaeological missions underway today but also an urgent one. Environmental challenges, notably the rising, corrosive saline groundwater—detected at 4-5 meters below the surface—are actively deteriorating this world heritage site. The Mataha-Expedition and its NRIAG report2 from April 2008 highlight how this water, exacerbated by modern irrigation and the Bahr Wahbi canal, threatens the structural integrity of both the Labyrinth and the adjacent pyramid, causing instability and obscuring deeper geophysical data. Time is of the essence: the hieroglyphs and paintings described by ancient authors risk being lost forever to salt crystal erosion if action is not taken swiftly.

The preservation of the Labyrinth and its pyramid is imperative, as is the continuation of research into this monumental structure, which may hold critical insights into our collective human past. The Mataha Expedition’s findings suggest that what Flinders Petrie identified as the Labyrinth’s foundation in 1888 might instead be its roof, with the true expanse of this subterranean wonder still awaiting full exploration. This is a global call to action—to safeguard a site that UNESCO has considered for "world heritage" status and to unlock the secrets of a building that could redefine our understanding of ancient civilizations.

We invite all seriously interested individuals, whether through financial support or expertise in archaeology, geophysics, preservation, or related fields, to join this vital mission. Please contact our Consortium for the Research and Preservation of the Egyptian Labyrinth3, to learn how you can contribute to preserving and uncovering this unparalleled testament to human history. Together, we can ensure that the Labyrinth of Egypt endures as a bridge to our ancient past, rather than becoming an empty relic of neglect.

For those interested in learning more about the modern efforts to explore the Labyrinth, the findings of the Mataha Expedition are detailed in the following document: labyrinthofegypt_com__printversion.pdf > [https://drive.google.com/file/d/1YqntaYOhvSWA7fd3jFYToPqx34odntjB/view]

Louis De Cordier > https://linktr.ee/louisdecordier

Consortium for the Research and Preservation of the Egyptian Labyrinth > https://linktr.ee/labyrinthofegypt