After grasping the true magnitude of Tim Akers’ satellite scans, a quiet urgency set it. We knew the implications stretched far beyond academic uproar. Fearing not only the backlash from the establishment but the wider dangers such revelations might trigger—disturbing interests well outside the bounds of archaeology—our research team made a crucial decision, one born of caution: to keep the findings secret.

We chose not to share any of the scan data outside our closed circle, implementing a strict non-disclosure agreement (NDA) for anyone granted access to the images. This wasn’t out of a desire to hoard information, but rather to protect the feasibility of our main goal: to carry out a new expedition on Egyptian soil.

We had learned from past experience—namely, the release of our scans associated with Dr Carmen Boulter and Klaus Dona1, and especially my own Mataha expedition scans in 20082—that making loud public claims only led to temporary media attention, followed by lasting obstacles. Keeping a low profile, rather than triggering a short-lived storm of speculation, would get us much further. Releasing the scans too early would risk blowing our cover with figures like Dr Zahi Hawass3 and the Ministry of Antiquities, potentially landing us on the infamous blacklist that barred the independent researcher Graham Hancock from entering Egypt for years.

I myself had already been placed on that blacklist once before—back in 2008—after presenting the Mataha expedition results during a lecture at Ghent University.4 Hawass interpreted this as a breach of national security protocol, simply for publicly sharing our geophysical results. I was determined not to repeat that experience. The Egyptian prison was not the type of labyrinth I wanted to get lost in. So we chose silence over spectacle. Our aim was to return to Egypt and explore the site properly. To do that, we had to remain invisible.

Harrogate, United Kingdom – 2015

Harrogate: the city where Tim Akers lived and the birthplace of Merlin Burrows5, his satellite scanning company. There they were—two trail-hardened researchers who had traveled the world in search of the fingerprints of Atlantis—awaiting check-in at the reception of the Crown Hotel6. Clearly excited about the upcoming meeting with the master of pixels, both were about to be guided into the ancient mysteries buried deep beneath the sands of Hawara: the lost Egyptian Labyrinth.

Harrogate, a town I had never heard of before, lies hidden among the green hills of North Yorkshire. A place forgotten by the outside world since the twilight of the British Empire, yet harboring a formidable technological secret. Just outside its medieval center stands RAF Menwith Hill, a Royal Air Force station7. Tim Akers knew it well. He had spent many years there as an officer in Special Access Programs (SAP), working with highly advanced and classified technologies.

Menwith Hill is no ordinary military base—it is the largest electronic monitoring station in the world. Buried deep beneath the peaceful façade of Harrogate, it operates as a satellite ground station, intercepting global communications, tracking Russian nuclear submarines, scanning for underground bunker complexes in Asia, and even locating landmines in the Middle East. It functions in close collaboration with the U.S. National Security Agency (NSA). A small town hiding a massive military eye. Akers had turned that military-grade expertise toward ancient mysteries—toward Hawara.

Montpellier Suite, 21 July 2015

For this special occasion, to present what Tim Akers had been silently analyzing since our webcam call in mid-June, Andrew Barker8 had rented a small conference room at the Crown Hotel—a 300-year-old establishment. The Montpellier Suite, with its wooden wainscoting, usually hosted corporate meetings. But on that day, it was to house one of the most extraordinary private briefings in the hotel’s history. Before we began, Michael Donnellan9—ever vigilant—swept the room thoroughly for hidden microphones or cameras. Michael, who had been part of our research team since the Carmen Boulter days, had taken it upon himself to visually document our daring quest for the Labyrinth.

Tension was palpable. Even Andrew, though already partially briefed as the project patron, had barely slept the night before. Seeking solace, he found himself in the downstairs pub, a glass of one of Scotland’s finest whiskies in hand, immersing himself in the verses of Kahlil Gibran's The Prophet10. The poetic reflections on life and the human condition offered a momentary escape. As he read, Michael animated the room with his tales of desert adventures and mysteries from the ancient world, his stories, gestures, and smiles weaving through the air and momentarily easing the weight of anticipation.

I wasn’t there myself. I was in Spain, filming a documentary about my high-altitude library project in the Sierra Nevada—Biblioteca del Sol—built years prior11. But everything at the Crown Hotel was filmed for archival purposes and for my later review.

Merlindown_Master.JPG

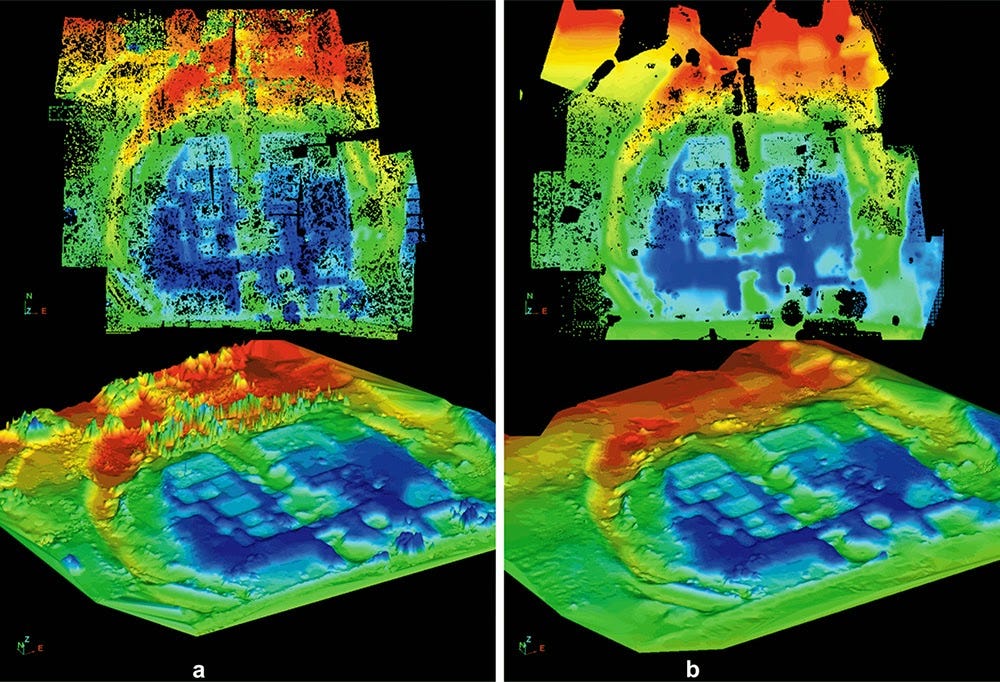

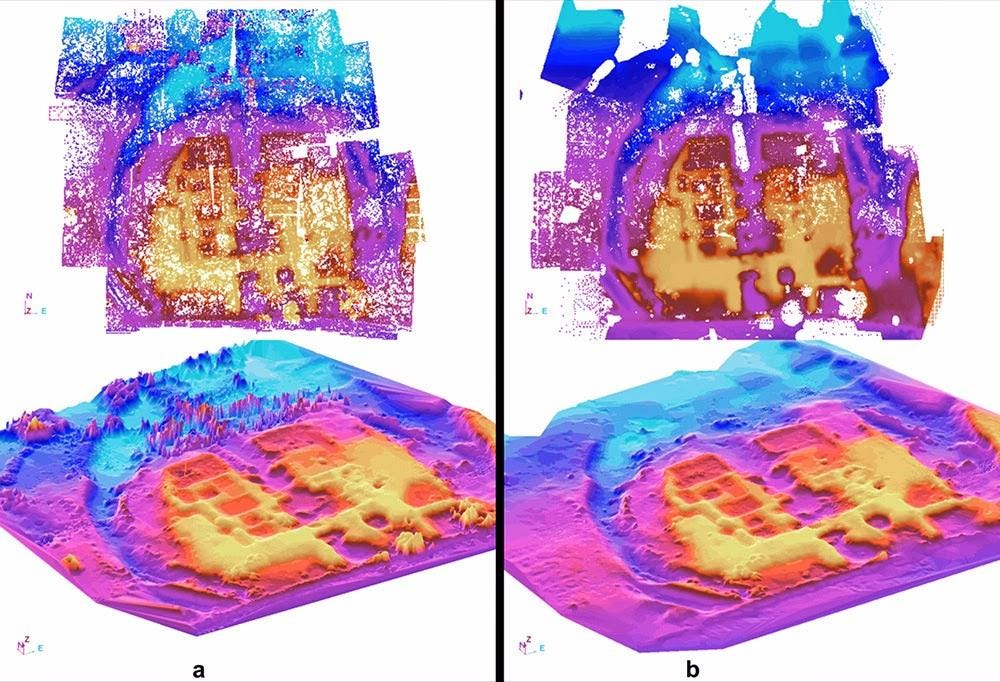

The room darkened. A projector lit up the first scan. “Do you recognize it?” Tim asked, with a mischievous grin. Everyone rushed toward the projector in the dim room. There it was, in full screen: the satellite scan of Hawara, now in full color and 3D. “You think you see it,” Tim said, “but you don’t!”

He had been immersed in these images for weeks and had a lifetime of satellite scan interpretation behind him. “There’s so much information in each image that your brain can’t absorb it all. You’re seeing five levels compressed into one. The color image gives a false sense of 3D—what appears on top is often the deepest layer.”

He explained the color code: “Black swaths are the default. Black shattered specks and dots are artifacts near the surface—likely from the Roman and Ptolemaic12 periods. Yellow is nearest to the top, then red, green, light blue, and finally dark blue at the deepest level.”

“This master image is a fusion of many overlapping satellite scans. Because the satellites don’t always fly directly over the site, we do deal with some minor distortions, which must be factored in when interpreting the exact positioning of elements. That said, the master composite provides a solid reference.”

A white-toned, inverted version of the scan was also shown, reversing the colors to offer a different visual interpretation.

“There are four distinct layers underground—five, if you include the surface above the mother rock,” Tim said. “These layers are separated by 20 to 50 meters and align, quite strikingly, with elements seen in the Hawara GeoSCAN survey13. These also showed four levels. However, my scans reveal a clearer separation between the top two layers and the bottom two.”

Given Andrew’s deep concern about the groundwater level—clearly visible in the entrance passage of the Pyramid of Hawara and currently obstructing any underground exploration—he posed the pressing question to Tim: “Does this mean we are dealing with an entirely submerged structure?”

“Not at all,” Tim replied. “It’s true that significant portions of the site are affected by shallow groundwater issues, but it’s important to stress—very shallow.”

Recent investigations, including those conducted by the Egyptian-Polish mission14, confirm that the groundwater does not penetrate deeply—reaching no more than approximately 8 meters below the surface, and certainly not down to the mother rock, which lies at a depth of around 18 meters.

The most affected area, Tim explained, is the zone surrounding the pyramid itself. There, the mudbrick structure acts almost like a wick, drawing moisture upward—even above the level of the canal that cuts across the site.

“The entire deeper understructure is free of water,” he emphasized. “And our scan data clearly shows it to be hollow.”

Dippy

“All layers converge at a central corridor or avenue,” he added, “like the atrium of a shopping mall, where you can see all floors from one vantage point.” A hall consisting of a massive space, 40 meters wide and no less than 100 meters long.15 “My personal interpretation,” Tim said, “is that this entire hall was constructed to house a centrally positioned, freestanding object about 40 meters long.”

“The central object is hard to classify—it appears metallic, not stone or wood. I named it ‘Dippy,’ after the giant Diplodocus skeleton in the Hintze Hall of London’s Natural History Museum. It could be anything—its shape resembles those tic-tac hard mints16, it might also be an upright disk, or even a colossal Shen Ring17: the ancient Egyptian symbol representing the eternal cycle of creation. That big object alone raises profound questions: How did it get there? Why is it there?”

He paused before adding with measured gravity: “A more speculative theory is that it’s some kind of portal—either interdimensional or interstellar —a stargate18. Its material signature is unlike anything I’ve seen in my entire career. But it’s there—undeniably there. I’ll let the future find out what Dippy is.”

Rising Closer to the Surface

“These deeper layers form an underground complex the size of ten football fields19. Closer to the surface, we notice a moat-like feature dug around the entire site, its shape unmistakably echoing the form of a Greek omega (Ω), or more significantly, the ancient Egyptian Shen ring —both symbols of eternal life —suggesting a deliberate, perhaps sacred, recurrence of the motif.”

“But was it a defensive moat filled with water, like in medieval castles? Or more like the recently discovered dry moat at Saqqara?20 The question remains.”

“Surrounding the pyramid are numerous peaks—deep shafts that seem to end in a chamber. These are likely Persian tomb shafts21—vertical burial structures from the Late Period, and the subsequent Persian Dynasty. That’s around the same time Herodotus visited Hawara!22”

These tomb shafts are known to reach depths of 30 meters, with side chambers carved at various depths and dimensions of up to 8 by 10 meters—testament to their monumental scale.

Returning to the Pyramid

Back at the pyramid of Hawara itself, the scans unmistakably show not one, but two chambers beneath the monument. One aligns with the well-known burial chamber uncovered by Flinders Petrie23 in January 1888. The second, still undiscovered, lies beyond, what Petrie described as the “blind passage.”24

This corridor, meticulously cut into the limestone bedrock, descends deep beneath the pyramid and was followed by Petrie until it abruptly terminated. At the time, he concluded that the tunnel led nowhere—an impression shaped by the groundwater he encountered within the Hawara pyramid, a persistent obstacle caused by the Bahr Wahbi canal25, an artificial waterway that cuts directly across the archaeological site. The rising water table made further excavation increasingly unfeasible.

He documented that the tunnel ended in what appeared to be a solid wall, with no immediate evidence of chambers beyond it. Yet, with the benefit of hindsight and new data, it’s plausible that Petrie reached not a definitive end, but rather a false terminus—a blocked transitional section, deliberately sealed or naturally obscured by the water.

This leads to a compelling hypothesis: that a hidden passage lies just beyond, forming a subterranean link between the pyramid and the deeper structures of Hawara.

Such a connection would not only align with the ancient testimony of Herodotus, who spoke of a tunnel joining the pyramid to the Labyrinth, but is also strongly supported by modern geophysical evidence. Both the Mataha Expedition (2008) and the joint Polish-Egyptian survey conducted by the University of Wrocław and Cairo University detected anomalies and voids in precisely this area—suggesting that Petrie may have stopped just short of one of the most significant buried features of the entire complex.

If verified, this would confirm that the “blind passage” does not mark an ending at all—but rather the hidden threshold to the legendary underground of Hawara: The lost labyrinth of Egypt….

In memory of Tim Akers, a man whose legacy transcends his titles as a military officer and satellite scan scientist. Tim was a visionary with an insatiable passion for ancient history, a walking encyclopedia whose knowledge illuminated the mysteries of the past. His heart burned for a better future for mankind, driven by an unyielding desire to push the boundaries of both technology and exploration. From the hidden depths of Hawara to the global stage of discovery, Tim’s work uncovered truths that challenged conventions and inspired awe. His curiosity, courage, and dedication to unraveling the secrets of our world will forever echo in the sands of time, a testament to a man who saw beyond the horizon and dared to dream of a greater tomorrow.

Zahi Abass Hawass (born May 28, 1947) is an Egyptian archaeologist, Egyptologist, and former Minister of Tourism and Antiquities (2011), and Secretary General of the Supreme Council of Antiquities (2002-2009). He has worked at archaeological sites in the Nile Delta, the Western Desert and the Upper Nile Valley. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Zahi_Hawass

Merlin Burrows is a UK-based satellite scanning and remote sensing company founded by Tim Akers. The company specializes in the use of advanced satellite imagery analysis to identify archaeological and geological anomalies across the globe. Headquartered in Harrogate, North Yorkshire, Merlin Burrows leverages proprietary techniques to detect hidden or forgotten structures beneath the Earth's surface, often focusing on sites of historical and cultural significance. Tim Akers, a former specialist with experience in classified technologies and satellite reconnaissance, trained the team in decoding complex data sets to reveal patterns invisible to the naked eye. https://www.merlinburrows.com/

The Crown Hotel, Harrogate, UK > https://www.crownhotelharrogate.com/

Royal Air Force Menwith Hill (RAF Menwith Hill) is a Royal Air Force station near Harrogate, North Yorkshire, England, which provides communications and intelligence support services to the United Kingdom and the United States. The site contains an extensive satellite ground station and is a communications intercept and missile warning site. It has been described as the largest electronic monitoring station in the world, as well as one of the world’s most secure buildings. For more information > https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/RAF_Menwith_Hill

Andrew Barker is a British writer and former corporate executive who played a pivotal role in funding key geophysical investigations at the Hawara archaeological site in Egypt. He was the patron of both the 2008–2009 surveys conducted by Geoscan Systems and later satellite-based analyses carried out by Merlin Burrows.

Barker previously resided in the Alpujarra region of southern Spain, where he developed a close partnership with artist and researcher Louis De Cordier. He now lives in Asturias, continuing his creative and exploratory pursuits.

Before dedicating himself to writing, Barker held senior roles in major technology and retail firms, including Xerox, Compaq, Siemens, and Virgin Retail. He was also a founder of GAME Ltd., a prominent UK video game retailer.

Since 2013, Barker has focused on his work as a poet and multimedia author. His "Poetry of Reportage" blends field photography and verse, often created in conflict zones and shared with local communities. His project The Ghosties explores themes of loss and memory through poetic storytelling.

Michael Donnellan, is an explorer, archaeologist, artist, VFX supervisor, film maker and the director of http://www.ingeniofilms.com/

The Prophet by Kahlil Gibran is a seminal work of spiritual literature, first published in 1923. Comprising 26 poetic essays, the book presents the wisdom of Almustafa, a prophet who shares profound insights on various aspects of life—including love, marriage, work, joy, sorrow, and death—before departing the city of Orphalese. Gibran's lyrical prose and philosophical depth have resonated with readers worldwide, making The Prophet one of the most translated and best-selling books of all time. Its universal themes and eloquent expression continue to inspire and offer solace to those seeking meaning and understanding in the human experience.

Biblioteca del Sol – A Culture Ark for Future Generations

Perched at 2000 meters in the Sierra Nevada of Southern Spain, the Biblioteca del Sol is a high mountain library and cultural repository developed by the Cosco Foundation under the vision of artist and researcher Louis De Cordier. Since its founding in 2009, the project has quietly amassed thousands of books, maps, blueprints, and even a seed bank, all sealed and preserved with the intention of safeguarding essential human knowledge through periods of disruption or collapse.

Far more than a time capsule, the library is conceived as a living archive—a contemporary sanctuary of art, science, and spirituality, resistant to digital decay and geophysical vulnerability. Built using advanced construction techniques and embedded within ancient Moorish terraces, the subterranean dome structure was designed to endure millennia, shielded from fire, water, war, and time.

In both spirit and structure, Biblioteca del Sol mirrors the mythic Egyptian Labyrinth described by Herodotus—a vast subterranean hall filled with sacred knowledge. Where the Labyrinth of Hawara may once have served as the "stone book of the ancients," this mountain library now stands as a modern echo: a solitary, durable vessel built to carry memory forward. Both spaces—one carved into the desert rock, the other nestled into a mountain—serve as cultural wombs, preserving the light of knowledge against the uncertainties of the age.

watch Time Capsule - 2016. A movie on the Biblioteca del Sol project - Sierra Nevada, Spain

The Ptolemaic Period (323–30 BCE): A Crossroads of Cultures

The Ptolemaic era in Egypt began with the death of Alexander the Great and the rise of Ptolemy I Soter, one of his generals, who established a Greco-Egyptian dynasty that lasted nearly 300 years. This period was marked by a unique fusion of Hellenistic and ancient Egyptian traditions, where Greek rulers adopted pharaonic titles and rituals while introducing new artistic, administrative, and religious elements to the Nile Valley.

The Ptolemaic age saw major architectural and cultural developments, with monumental temples, papyri, and city plans reflecting a hybrid worldview. It was also a time of heightened intellectual activity, with the famed Library of Alexandria serving as a beacon of learning.

At Hawara, the Ptolemaic period left visible traces, particularly in the uppermost archaeological layers. Roman and Ptolemaic artifacts—including funerary objects, pottery, and building remnants—have been found scattered near the surface. More significantly, it is believed that during this era, the site of the Labyrinth was revisited or repurposed, possibly as a necropolis. The famed Fayum portraits, painted during the Ptolemaic and Roman periods, have been uncovered in the region around Hawara, testifying to the area’s continued importance as a burial ground and spiritual site during this era of cultural convergence.

Hawara GeoSCAN survey. The Hawara satellite scanning funded and commissioned in 2014 by Andrew Barker, with the assistance of Dr Carmen Boulter and the help of her friend Klaus Dona, executed by the physicist Timo Glowatzki and his GeoSCAN company (https://www.geoscansystems.de/ ). For more info on how it all came about read >

Egyptian-Polish mission 2008-2009 > https://wisdomofnations.com/egypt/hawara/hawara-research-2008-2009-report/

Erratum – Dimensional Revision:The previously cited spatial dimensions of the central atrium and adjoining chamber (64 × 160 m atrium) were based on the original data available in 2015 to Louis De Cordier. Subsequent analysis by Merlin Burrows employing updated reference points and refined spatial calibration, revised these figures to an atrium of approximately 40 meters wide by 100 meters long, retaining the symbolic 5:2 proportion. These corrections reflect a more accurate interpretation of the spatial configuration, ensuring consistency with both the architectural context and the latest digital reconstruction methodologies. The author acknowledges the earlier overestimation and welcomes this clarification as part of the evolving understanding of the site.

The “Tic Tac” Phenomenon: From Mint to Mystery

The term “Tic Tac” has become an unexpected touchstone in contemporary discussions of Unidentified Aerial Phenomena (UAPs). It refers to the iconic, oblong, white candy mint—smooth, rounded, and silently aerodynamic in shape. This visual became part of the global lexicon following the 2004 U.S. Navy incident off the coast of San Diego, in which fighter pilots encountered a fast-moving, featureless, white object resembling a giant “Tic Tac.”

The craft was described as approximately 40–50 feet long, with no visible propulsion system, wings, or exhaust. It moved with sudden acceleration, hovered with stability, and exhibited flight behavior well beyond the capabilities of known human technology. Multiple sensors confirmed its presence, and footage of the encounter—later declassified—sparked serious interest within the Pentagon’s UAP programs.

Since then, “Tic Tac” has become shorthand for a class of mysterious aerial objects—sleek, silent, and possibly transmedium—that have been observed globally. Its simple, almost mundane visual comparison to a mint belies its profound implications: a familiar object now serves as the visual cipher for one of the greatest technological enigmas of our time.

The Shen Ring: Eternal Cycle, Digital Guardian

The Shen Ring, one of the most profound symbols in ancient Egyptian cosmology, represents eternity, protection, and the cyclical nature of creation. Formed as a perfect loop of rope with the ends tied together, it symbolizes a universe held intact by divine order—unbroken, unending, and protected from the chaos of dissolution. Often depicted beneath the feet of deities or encircling royal names (cartouches), the Shen Ring signified the sacred containment of life, time, and sovereign destiny.

In Egyptian myth, it stands as a metaphysical safeguard against Nun, the primordial watery abyss of chaos. To wear or inscribe the Shen was to reaffirm cosmic balance and shield one’s spirit across the thresholds of life, death, and rebirth.

Building upon this ancient esoteric tradition, the Cosco Foundation co-created a series of 12 Crypto Amulets—blockchain-based talismans that echo the symbolic power of Egypt’s magical artifacts. In this collection, the Shen Ring of Power is reimagined as a digital amulet—a guardian of the eternal creative spirit in the age of the metaverse. It offers “infinite protection against the primordial chaos,” a poetic continuity between ancient myth and the new digital ether.

Developed in collaboration with meta-architect Leonardo Marchesi, the collection was designed as a fundraiser for the exploration of the legendary Egyptian Labyrinth—one of the most enigmatic sites of human heritage. Each amulet was minted on the Ethereum blockchain in a limited edition of 1,111, and can be acquired on OpenSea, the largest decentralized marketplace for NFTs.

→ Crypto Amulet Collection: opensea.io/collection/crypt0amulets

→ The Shen Ring of Power: Buy NFT on OpenSea

✉ For guided acquisition support, feel free to contact us. ⟠

Circular Ring Stargates and the Legacy of a Lost Civilization

A circular ring stargate is a theoretical or speculative device believed to enable instantaneous travel between distant points in space—or even across dimensions—through a fixed, often metallic or crystalline, portal structure. Popularized in science fiction yet rooted in ancient myths, these ring-like constructs are often imagined as gateways used by advanced civilizations for exploration, evacuation, or interstellar contact.

The concept gains further intrigue when placed within the context of alternative historical theories proposing the existence of a sophisticated, pre-diluvian civilization that flourished during or before the last Ice Age—roughly 12,000 years ago. This hypothetical culture, often referenced in connection with Plato’s Atlantis or the global flood myths found in Sumerian, Egyptian, and Mesoamerican records, is believed by some to have possessed technologies far exceeding those of early historic societies.

If such a civilization did exist, it’s conceivable that remnants of its infrastructure—buried under sediment, ice, or millennia of reconstruction—might include anomalous structures resembling stargates. These circular, free-standing forms, if discovered in ancient architectural complexes, might not be symbolic or decorative alone, but remnants of functional systems for energetic transmission or long-distance transit.

While no definitive archaeological evidence currently supports the existence of stargate technology, the enduring presence of circular portals in the iconography of megalithic sites—from the stone “doors” of Puma Punku to Egyptian “shen” and “ankh” symbols—invites continued exploration of whether these shapes encoded deeper technical or metaphysical knowledge.

The Scale of the Hawara Labyrinth: Ten Football Fields Wide

The foundation discovered by British archaeologist Flinders Petrie in 1888 at Hawara measured approximately 304 by 244 meters—a footprint of monumental proportions. To grasp its scale in modern terms, this area is roughly equivalent to the size of ten standard football fields placed side by side.

Petrie’s findings supported ancient accounts, such as those of Herodotus and Strabo, which described a vast underground structure—often referred to as the Egyptian Labyrinth—believed to have served as a temple, archive, or necropolis of extraordinary complexity.

This comparison highlights the sheer ambition and scale of the original structure, most of which remains buried beneath layers of sediment, awaiting full exploration

The Dry Moat of Saqqara: A Monumental Boundary of Initiation

In recent years, archaeological teams working at Saqqara—the vast necropolis of ancient Memphis—have uncovered the remains of an enormous dry moat encircling the Step Pyramid of Djoser. Unlike traditional moats filled with water for defensive purposes, this trench-like structure was cut directly into the limestone bedrock and measures several meters deep and wide, extending for hundreds of meters.

Scholars now interpret the moat not as a fortification, but as a symbolic and ritual boundary—a liminal zone demarcating the realm of the living from the realm of the divine and the dead. Its complex, winding paths may have functioned as part of an initiation journey for the soul of the deceased pharaoh, echoing mythic themes of passage, purification, and rebirth central to ancient Egyptian cosmology.

The Saqqara moat is one of the oldest known monumental constructions of its kind, and its discovery has reshaped our understanding of early dynastic funerary architecture, suggesting that large-scale symbolic boundaries were integrated into sacred sites as early as the 3rd Dynasty (c. 27th century BCE).

Persian Tomb Shafts at Hawara: Signs of a Late Period Necropolis

During the Late Period of ancient Egypt—particularly under the 26th Dynasty (Saite) and the subsequent 27th Dynasty (the First Persian Period, c. 525–404 BCE)—a distinct type of burial architecture emerged: the deep vertical shaft tomb. These tombs, often reaching depths of 20 to 30 meters, were typically cut directly into the bedrock and contained multiple side chambers branching off at various levels. The shafts were designed for elite burials and often reused or expanded across generations.

Such tombs are well-documented at Saqqara, Abydos, and Giza, and have been linked to the administrative and religious elite of the time, including high priests, generals, and Persian officials. Their design reflects both a reverence for older burial customs and the increasing complexity of underground necropoleis in the Late Period.

Given that Herodotus visited Hawara around the same period and described an expansive and mysterious complex, it is very plausible that Hawara served not only as a monumental cult site but also as an active Late Period necropolis. If confirmed through excavation, these shafts could significantly expand our understanding of the site's multi-period use and its importance during Persian rule in Egypt.

The Hawara pyramid blind passage. During his 1888 excavation of the pyramid of Amenemhat III at Hawara, British archaeologist Flinders Petrie encountered a descending passage that came to be referred to as “blind passage”, a death-end tunnel. This corridor, cut deep into the limestone bedrock, extended beneath the pyramid structure but eventually reached a point where further progress was halted.

Petrie concluded that the tunnel led nowhere, largely because he encountered groundwater which made excavation increasingly difficult. The waterlogged conditions inside the pyramid prevented him from pursuing the passage any further. He documented that the tunnel ended in what appeared to be a solid wall, with no immediate evidence of chambers beyond it.

Bahr Wahbi canal - The construction of the Bahr Wahbi canal, directed by French engineer Linant de Bellefonds between 1830 and 1835, significantly impacted the Hawara Necropolis. Though not classified as an archaeological expedition, Linant de Bellefonds, driven by archaeological interests, likely intentionally routed the canal to cross the labyrinth area, acting as a giant archaeological cross-section and unearthing many antiquities. Linant de Bellefonds' canal construction (1830--1835) crossed the Hawara Necropolis, likely intentionally due to his archaeological interests and the pyramid's higher elevation. While it unearthed antiquities, it did not reach the depth of Petrie’s alleged labyrinth foundation, leaving it untouched. This canal is a major cause of elevated water levels within the pyramid today. However, the canal did not reach the depth of Petrie’s alleged labyrinth foundation, leaving it undisturbed.